More rarely, yet now and again, a disease itself is new. That this does not happen is manifestly untrue, for in our time a lady, from whose genitals flesh had prolapsed and become gangrenous, died in the course of a few hours, whilst practitioners of the highest standing found out neither the class of malady nor a remedy. I conclude that they attempted nothing because no one was willing to risk a conjecture of his own in the case of a distinguished personage, for fear that he might seem to have killed, if he did not save her;[p. 29] yet it is probable that something might possibly have been thought of, had no such timidity prevailed, and perchance this might have been successful had one but tried it.

Ancient Greek and Roman Medical Instruments

Michael Lahanas

http://www.mlahanas.de/Greeks/MedicalInstruments.htm

Hooks, bone drills, and catheters

Vaginal speculum, scalpels, and forceps

Many medical practices from antiquity have been done away with, bloodletting being a notable example, but also more obscure practices such as the Hippocratic bench for spine alignment depicted below.

Medical practices such as splint setting and surgery itself, such as amputations and even more complicated procedures such as rhinoplasty and removal of cataracts were all common practice and and had a well established history despite the lack of a philosophical understanding of the underlying biological mechanisms. In the book Ancient Inventions Peter James and Nick Thorpe discuss the similarity of surgical practices throughout this development of medical philosophy and even in their common applications today. Nearly identical techniques for rhinoplasty and cataract removal appeared in Hindu texts nearly half a millennium earlier than in Greek and Roman medical treatises, suggesting the borrowing of procedures across cultures. Very similar basic tools and procedures had been applied for nearly three millennia up until the last hundred or so years. Medical experimentation on humans, such as the Nazis during WWII, have largely been atrocities due to the invasiveness and often sadism of procedures. Medical practice in general has actually been largely conservative.

Though practices stayed relativity constant ideas were constantly fluctuating. The 2nd century Greek philosopher Celsus largely summarized Greek and Roman advances over this time period in his medical encyclopedia De Medicina, in the Prooemium the developing beliefs of the philosophers involved are detailed;

At first the science of healing was held to be part of philosophy, so that treatment of disease and contemplation of the nature of things began through the same authorities; clearly because healing was needed especially by those whose bodily strength had been weakened by restless thinking and night-watching.

Art of Medicine was divided into three parts: one being that which cures through diet( Διαιτητικήν), another through medicaments(Φαρμακευτικήν), and the third by hand(Χειρουργίαν).

Homer (Greek ~850 BC, Trojan war 1190-1180 BC) stated, however, not that they gave any aid in the pestilence or in the various sorts of diseases, but only that they relieved wounds by the knife and by medicaments…diseases were then ascribed to the anger of the immortal gods, and from them help used to be sought

On adverse health:

At first the science of healing was held to be part of philosophy, so that treatment of disease and contemplation of the nature of things began through the same authorities; clearly because healing was needed especially by those whose bodily strength had been weakened by restless thinking and night-watching.

Art of Medicine was divided into three parts: one being that which cures through diet( Διαιτητικήν), another through medicaments(Φαρμακευτικήν), and the third by hand(Χειρουργίαν).

Homer (Greek ~850 BC, Trojan war 1190-1180 BC) stated, however, not that they gave any aid in the pestilence or in the various sorts of diseases, but only that they relieved wounds by the knife and by medicaments…diseases were then ascribed to the anger of the immortal gods, and from them help used to be sought

many who professed philosophy became expert in medicine, the most celebrated being Pythagoras (Ionian Greek philosopher 570-495 BC), Empedocles (490-430 BC, Greek, cosmogenic theory of the four classical elements) and Democritus (460-370 BC, Greek, formulated atomic theory of the cosmos with his mentor Leucippus). But it was, as some believe, a pupil of the last, Hippocrates of Cos (460-370 BC, Greek, father of western medicine), a man first and foremost worthy to be remembered, notable both for professional skill and for eloquence, who separated this branch of learning from the study of philosophy. After him Diocles of Carystus (4th BC, importance of diet, wrote treatises in Attic opposed to customary Ionic), next Praxagoras (born ~340 BC, insisted on 11 humors, distinguished arteries and veins) and Chrysippus (279-206 BC, Greek, stoic, determinist, organic unity of the universe; correlation and mutual interdependence between all its parts) then Herophilus (335-280 BC, Greek, pupil of praxagoras, discovered sensory and motor nerves, cofounder of the medical school of Alexandria) and Erasistratus (304-250 BC, Greek, cofounder of medical school of Alexandria, discovered the role of the heart) so practised this art that they made advances even towards various methods of treatment. Apollonius and Glaucias, and somewhat later Heraclides of Tarentum (2nd BC, Greek, extensively quoted by Galen, only wrote what he himself found to be right; Empirici or Experimentalists) They believe it impossible for one who is ignorant of the origin of diseases to learn how to treat them suitably.

On adverse health:

Herophilus; all the fault is in the humours

Hippocrates; or in the breath

Erasistratus; blood is transfused into those blood-vessels which are fitted for pneuma, and excites inflammation which the Greeks term φλεγμόνην, and that inflammation effects such a disturbance as there is in fever

Asclepiades; little bodies by being brought to a standstill in passing through invisible pores block the passage

On Digestion:

Erasistratus held that in the belly the food is ground up

Plistonicus, a pupil of Praxagoras, that it putrefies

Hippocrates, that food is cooked up by heat.

Asclepiades, who propound that all such notions are vain and superfluous, that there is no concoction at all, but that material is transmitted through the body, crude as swallowed

On Causation and Treatment

Themison, (1st BC, founder of the Methodic school of medicine) contend that there is no cause whatever, the knowledge of which has any bearing on treatment: they hold that it is sufficient to observe certain general characteristics of diseases;

if Erasistratus had been sufficiently versed in the study of the nature of things, as those practitioners rashly claim themselves to be, he would have known also that nothing is due to one cause alone,

Erasistratus himself, who says that fever is produced by blood transfused into the arteries, and that this happens in an over-replete body, failed to discover why, of two equally replete persons, one should lapse into disease, and the other remain free

Hippocrates said that in healing it was necessary to take note both of common and of particular characteristics.

Cassius, the most ingenious practitioner of our generation, recently dead, in a case suffering from fever and great thirst, when he learnt that the man had begun to feel oppressed after intoxication,[p. 39] administered cold water, by which draught, when by the admixture he had broken the force of the wine, he forthwith dispersed the fever by means of a sleep and a sweat.

Submission to the uncontrollable will of the Gods, however, began losing favor with the implementation of Hippocratic medicine. Hippocrates was one of the earliest Greek philosophers to start contemplating the functions of biological processes in attempting to apply medical practices. In his treatise Nutriment he largely postulates on the mechanisms of digestion;

Apparently nutritive food is supposed to be dissolved in moisture, and thus to be carried to every part of the body, assimilating itself to bone, flesh, and so

Air (breath) also is regarded as food, passing through the arteries from the heart, while the blood passes through the veins from the liver. But the function of blood is not understood ; blood is, like milk, "what is left over" (πλεονας1μός2) when nourishment has taken place.

These paraphrases on sections from Nutriment demonstrate both an application of intuition, and a profound lack of information on many of the bodies function. Food, both the soluble and insoluble, indeed must be dissolved in moisture before being carried to the rest of the body. Solvation is the medical term for breaking up large aggregations of lipids into tiny lipid droplets, which can then be packaged with soluble lipoproteins for transport to the rest of the body through the blood. The roll of blood as that “moistening” medium, however, apparently went overlooked. More important than philosophical conjecture, he was also one of the first to compile detailed descriptions of the circumstances of diseases, and there variations. In De morbis popularibus, on the epidemics he comments on many factors surrounding a tuberculosis epidemic, then known as phthisis (Greek for dwindling or wasting away);

IN THASUS, about the autumn equinox, and under the Pleiades, the rains were abundant, constant, and soft, with southerly winds; the winter southerly, the northerly winds faint, droughts; on the whole, the winter having the character of spring. The spring was southerly, cool, rains small in quantity. Summer, for the most part, cloudy, no rain, the Etesian winds, rare and small, blew in an irregular manner. The whole constitution of the season being thus inclined to the southerly, and with droughts early in the spring, from the preceding opposite and northerly state, ardent fevers occurred in a few instances, and these very mild, being rarely attended with hemorrhage, and never proving fatal

They were of a lax, large, diffused character, without inflammation or pain, and they went away without any critical sign

Many had dry coughs without expectoration, and accompanied with hoarseness of voice. In some instances earlier, and in others later, inflammations with pain seized sometimes one of [p. 101]the testicles, and sometimes both; some of these cases were accompanied with fever and some not

The urine was thin, colorless, unconcocted, or thick, with a deficient sediment, not settling favorably, but casting down a crude and unseasonable sediment.

In the course of the summer and autumn many fevers of the [p. 102]continual type, but not violent; they attacked persons who had been long indisposed, but who were otherwise not in an uncomfortable state.

Within these passages, the beginning of widespread medical categorization and compilation begins to be evident. Both the spectrum of conditions and their chronology is taken into account. Large scale data collection of this sort, however, didn’t prove particularly enlightening until the 1850’s with the invent of epidemiology. John Snow is attributed as the farther of epidemiology for his role in understanding the underlying reasons for the 1854 cholera outbreak in England. He assembled huge amounts of data on the eating, drinking, and hygiene habits of both sick and healthy individuals during the epidemic, ultimately tracing the outbreak back to a contaminated well. The Book Ghost Map by Steve Johnson describes the context surrounding this paradigm shift. Previously, miasma theories, derived from the greek term for pollution, were most commonly accepted. The notion of disease being transmitted through polluted air dates back to Hippocrates who was obsessed with air quality.

His treatise On Air, Water, and Places begins : “whoever wishes to investigate medicine properly, should proceed thus: in the first place to consider the seasons fo the year, and what effects each of them produces for they are not all alike, but differ much from themselves in regard to their changes. Then the winds, the hot and the cold, especially such as are common to all countries, and then such as are peculiar to each locality.”

His treatise On Air, Water, and Places begins : “whoever wishes to investigate medicine properly, should proceed thus: in the first place to consider the seasons fo the year, and what effects each of them produces for they are not all alike, but differ much from themselves in regard to their changes. Then the winds, the hot and the cold, especially such as are common to all countries, and then such as are peculiar to each locality.”

In 1853 miasma theories were still eminently compatible with religious traditions. Henry Whitehead, a man of the cross, attributed the Golden Square outbreak to God’s will. Even the revolutionist Victorians also clung to miasmic theory. Belief in miasmic theory likely largely resulted from authors' visceral disgust with the smells of the city. No science or statistics of time, however, suggested smell alone was killing London’s people.

John Snow’s detailed rigorous analysis of the water companies and the transmission routes of the Horsleydown outbreak couldn’t compete with a whif of the air in Bermondsey district which wreaked with the stench of decaying corpses. Telescopes and Microscopes had been around for 200 years but the idea of microbes causing disease was still unheard of. Instead theories such as Thomas Sydenham’s internal-constitution theory of the epidemic, an eccentric hybrid of weather forecasting and medieval humorology, were common. He posited that Certain atmospheric conditions encouraged specific types of disease, and predisposition to infection lay in the sufferers themselves. Eventually, however, John Snow's Veronoi diagram, shown below, illustrated the pump as the primary suspect for the outbreak.

|

| Black bars represent deaths, and the grey line represents the border where walking distance to Broad Street pump is closer than other pumps. |

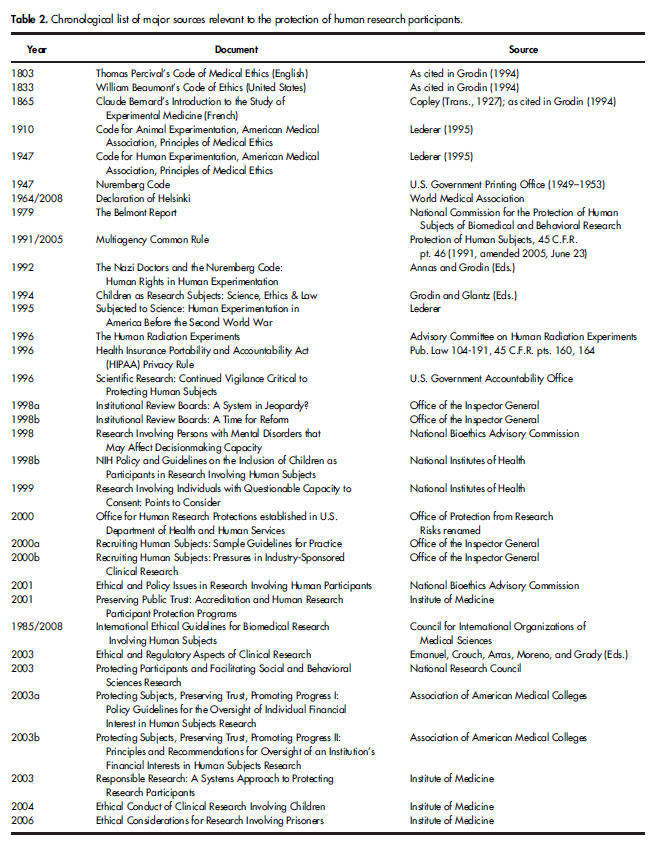

Despite the relatively conservative nature of medical practice many regulations on research ethics have only rather recently been imposed. Jennifer Horner outlines these advances in her paper Research Ethics I: Responsible Conduct of Research (RCR)—Historical and Contemporary Issues Pertaining to Human and Animal Experimentation

Modern medicine, however, has seemingly moved away from this conservative nature with new experimental drugs on the market almost daily with very little research on their lasting and indirect effects. Rather than the long standing model concisely put by Celsus in which;

the Art of Medicine was not a discovery following upon reasoning, but after the discovery of the remedy, the reason for it was sought out.

Modern man has begun attempting reason as a means for discovering a remedy.

Ben - Sarah pointed me to this great article which not only has a list of tools that have been found from the first to fourth centuries AD, but also has detailed explanations from Celsus (2nd century Greek philosopher). While I think your post did a phenomenal job showcasing the tools that were used, I think this article and future research on the topic can maybe elucidate the class about the philosophy behind these tools, such as the ones that were used for bloodletting. Also, I think it might be interesting to compare how the ancients experimented on humans and animals and how it is done today. While informed consent is absolutely required to be published in a reputable journal today, there are countries which do not obey these standards and experiment illegally (maybe comparing the experiments of Hitler's regime etc). The article's link is provided below.

ReplyDeletehttp://www.ucl.ac.uk/~ucgajpd/medicina%20antiqua/sa_ArchaeologicalRemains.pdf