1) Anita Guerrini. Experimenting with Humans and Animals; From Galen to Animal Rights Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore (2003)

Summary A broad overview of experimental and medical development from the 3rd BCE until modern day, including understanding anatomy through vivisection and disease as microscopic molecular disorders and their application to surgery and vaccination is discussed.

3) Maud Gleason. Shock and Awe: the performance dimension of Galen's anatomy demonstrations (2007) Princeton/Stanford Working papers in classics

Summary Galen's dissection demonstrations are described with a focus on the performance aspects used by Galen to enhance his reputation. Some more notorious stories including his dissection and resuscitation of an Ape are recalled, and the tools and techniques used are described.

2) Peter James and Nick Thorpe. Ancient Inventions (1994) Random House publishing group, NY.

Summary I focused on descriptions of the tools and techniques employed for ancient techniques including couching of cataracts, reconstructive surgery, and denture construction and fixation.

3) JR Kirkup. The history and evolution of surgical instruments II:Origins: function: carriage: manufacture Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England (1982) vol. 64

Summary An overview of instrumental development from primitive substitutions of shell or bone for teeth, and shaping of metal rods into simple surgical tools, and developments leading to more complicated fabrications.

4) John Stewart Milne. Surgical Instruments in Greek and Roman Times. Claredon Press: Oxford, 1907.

Summary Complementing resource for comparing an early 20th CE dissertation on ancient surgical instruments to the late 20th CE reference above.

5) John Michalczyk. In the Shadow of the Reich: Nazi Medicine (1997)

Summary This documentary describes the rise of the Nazi regime. The steps leading up to the implementation of their "final solution" are presented, starting with mandatory sterilization for the mentally retarded modeled after preceding American legislation, the concept of "social hygiene" and purification, the role of doctors in ghettos, and the inhumane "science" of death camps.

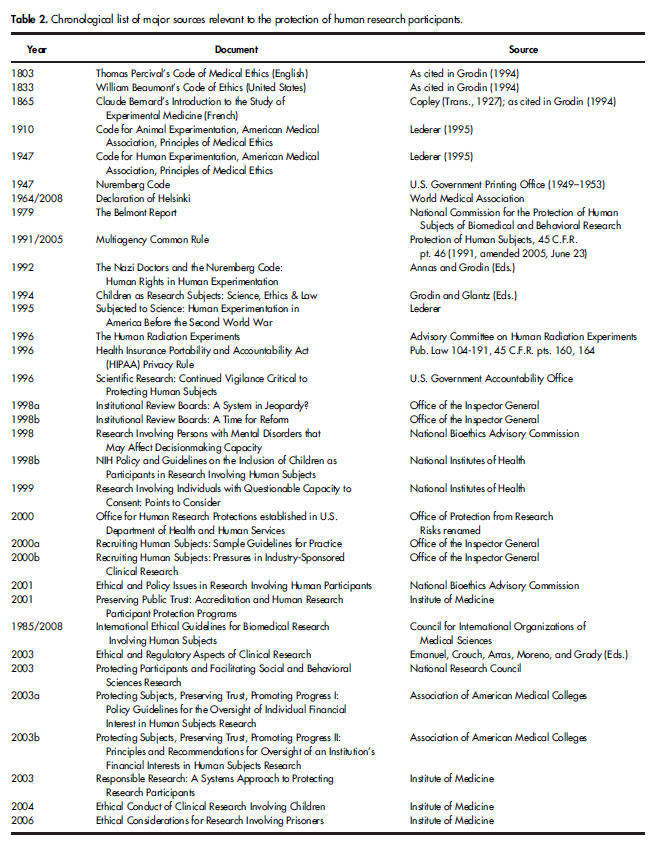

6) J Horner, FD Minifie. Research Ethics I: Responsible Conduct of Research (RCR)—Historical and Contemporary Issues Pertaining to Human and Animal Experimentation Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research; Vol. 54, S303–S329 (2011)

Summary The chronological order of major legislation and developments in research ethics, largely in the last two centuries, are cataloged in this article supplement.

7) Steven Johnson. The Ghost Map. Riverhead Books: NY (2006)

Summary The 1850's cholera outbreak in London is described and the mentality of major figures and ideas of its cause are outlined. Most notably, John Snow's medical methodology involving large scale cataloging of lifestyles surrounding affected versus unaffected individuals, tracing the outbreak back to a sewage contaminated pump, and discovery of microscopic infectious agents is presented.

8) S Mukhopadhyay, GC Layek. Analysis of blood flow through a modelled artery with an aneurysm Applied Mathematics and Computation Volume 217, Issue 16, 15 (2011) 6792-6801

Abstract The intention of the present work is to carry out a systematic analysis of flow features in a tube, modelled as artery, having a local aneurysm in presence of haematocrit…. the numerical illustrations presented in this paper provide an effective measure to estimate the combined influence of haematocrit and aneurysm on flow characteristics.

9) John Cullis, John Hudson and Philip Jones A Different Rationale for Redistribution: Pursuit of Happiness in the European Union Journal of Happiness Studies Volume 12, 2, (2011) 323-341

Abstract This paper considers the role of redistribution in the light of recent research findings on self reported happiness. The analysis and empirical work reported here tries to relate this to a representative actor ‘homo realitus’ and the ‘pursuit of happiness’ rather than the traditional ‘homo economicus’. Econometrically estimating the determinants of happiness in the European Union (EU) using Eurobarometer data and the construction of an ‘Index of Happiness’ facilitates policy simulations. Such simulations find that in terms of average happiness there is little advantage to redistributing income within a country, but more from redistributing income between countries. The importance for happiness of relative income, average standard of living, marital status and age are confirmed. The theoretical rationale for redistribution is also examined.

Abstract Virtual compound screening using molecular docking is widely used in the discovery of new lead compounds for drug design. However, this method is not completely reliable and therefore unsatisfactory. In this study, we used massive molecular dynamics simulations of protein-ligand conformations obtained by molecular docking in order to improve the enrichment performance of molecular docking. Our screening approach employed the molecular mechanics/Poisson-Boltzmann and surface area method to estimate the binding free energies....This result indicates that the application of molecular dynamics simulations to virtual screening for lead discovery is both effective and practical. However, further optimization of the computational protocols is required for screening various target proteins.

11) KL Steinmetz, EG Spack.

The basics of preclinical drug development for neurodegenerative disease indications (2007)

http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2697630

Abstract Preclinical development encompasses the activities that link drug discovery in the laboratory to initiation of human clinical trials. Preclinical studies can be designed to identify a lead candidate from several hits; develop the best procedure for new drug scale-up; select the best formulation; determine the route, frequency, and duration of exposure; and ultimately support the intended clinical trial design. The details of each preclinical development package can vary, but all have some common features. Rodent and nonrodent mammalian models are used to delineate the pharmacokinetic profile and general safety, as well as to identify toxicity patterns. One or more species may be used to determine the drug's mean residence time in the body, which depends on inherent absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion properties...

12) Kuntz.

Structure-based strategies for drug design and discovery (1992) Science 257 pg 1078-82

13)

Rebecca White.

Drugs and nutrition: how side effects can influence nutritional intake (2010) Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 69, 558-564

Abstract There are many factors that can influence nutritional intake. Food availability, physical capability, appetite, presence of gastrointestinal symptoms and perception of food are examples. Drug therapy can negatively influence nutritional intake through their effect on these factors, predominantly due to side effects. This review aims to give a brief overview of each of these factors and how drug therapy can affect them.

Selected Excerpts from Primary Sources Galen On The Natural Faculties 1.15

Here let us forget the absurdities of Asclepiades, and, in company with those who are persuaded that the urine does pass through the kidneys, let us consider what is the character of this function. For, most assuredly, either the urine is conveyed by its own motion to the kidneys, considering this the better course (as do we when we go off to market!1), or, if this be impossible, then some other reason for its conveyance must be found. What, then, is this? If we are not going to grant the kidneys a faculty for attracting this particular quality,2 as Hippocrates held, we shall discover no other reason. For, surely everyone sees that either the kidneys must attract the urine, or the veins must propel it. Celsus De Medicina Book 1, Prooemium

Homer stated, however, not that they gave any aid in the pestilence or in the various sorts of diseases, but only that they relieved wounds by the knife and by medicaments. Hence it appears that by them those parts only of the Art were attempted, and that they were the oldest.[p. 5] From the same authority, indeed, it can be learned that diseases were then ascribed to the anger of the immortal gods, and from them help used to be sought; and it is probable that with no aids against bad health, none the less health was generally good because of good habits, which neither indolence nor luxury had vitiated: since it is these two which have afflicted the bodies of men, first in Greece, and later amongst us; and hence this complex Art of Medicine, not needed in former times

At first the science of healing was held to be part of philosophy, so that treatment of disease and contemplation of the nature of things began through the same authorities; clearly because healing was needed especially by those whose bodily strength had been weakened by restless thinking and night-watching. Hence we find that many who professed philosophy became expert in medicine, the most celebrated being Pythagoras, Empedocles and Democritus. But it was, as some believe, a pupil of the last, Hippocrates of Cos, a man first and foremost worthy to be remembered, notable both for professional skill and for eloquence, who separated this branch of learning from the study of philosophy. After him[p. 7] Diocles of Carystus, next Praxagoras and Chrysippus, then Herophilus and Erasistratus, so practised this art that they made advances even towards various methods of treatment.

he Art of Medicine was divided into three parts: one being that which cures through diet, another through medicaments, and the third by hand. The Greeks termed the first Διαιτητικήν, the second Φαρμακευτικήν, the third Χειρουργίαν. Apollonius and Glaucias, and somewhat later Heraclides of Tarentum, and other men of no small note, who in accordance with what they professed called themselves Empirici (or Experimentalists)

For they believe it impossible for one who is ignorant of the origin of diseases to learn how to treat them suitably. They say that it does not admit of doubt that there is need for differences in treatment, if, as certain of the professors of philosophy have stated, some excess, or some deficiency, among the four elements, creates adverse health; or, if all the fault is in the humours, as was the view of Herophilus; or in the breath, according to Hippocrates; or if blood is transfused into those blood-vessels which are fitted for pneuma, and excites inflammation[p. 11] which the Greeks term φλεγμόνην, and that inflammation effects such a disturbance as there is in fever, which was taught by Erasistratus; or if little bodies by being brought to a standstill in passing through invisible pores block the passage, as Asclepiades contended — his will be the right way of treatment, who has not failed to see the primary origin of the cause Some following Erasistratus hold that in the belly the food is ground up; others, following Plistonicus, a pupil of Praxagoras, that it putrefies; others believe with Hippocrates, that food is cooked up by heat. In addition there are the followers of Asclepiades, who propound that all such notions are vain and superfluous, that there is no concoction at all, but that material is transmitted through the body, crude as swallowed

the Art of Medicine was not a discovery following upon reasoning, but after the discovery of the remedy, the reason for it was sought out

More rarely, yet now and again, a disease itself is new. That this does not happen is manifestly untrue, for in our time a lady, from whose genitals flesh had prolapsed and become gangrenous, died in the course of a few hours, whilst practitioners of the highest standing found out neither the class of malady nor a remedy. I conclude that they attempted nothing because no one was willing to risk a conjecture of his own in the case of a distinguished personage, for fear that he might seem to have killed, if he did not save her;[p. 29] yet it is probable that something might possibly have been thought of, had no such timidity prevailed, and perchance this might have been successful had one but tried it.

Themison, contend that there is no cause whatever, the knowledge of which has any bearing on treatment: they hold that it is sufficient to observe certain general characteristics of diseases; that of these there are three classes, one a constriction, another a flux, the third a mixture. For the sick at one time excrete too little, at another time too much; again, from one part too little, from another too much

But if Erasistratus had been sufficiently versed in the study of the nature of things, as those practitioners rashly claim themselves to be, he would have known also that nothing is due to one cause alone, but that which is taken to be the cause is that which seems to have had the most influence

Erasistratus himself, who says that fever is produced by blood transfused into the arteries, and that this happens in an over-replete body, failed to discover why, of two equally replete persons, one should lapse into disease, and the other remain free from anything dangerous

Hippocrates, said that in healing it was necessary to take note both of common and of particular characteristics.

Cassius, the most ingenious practitioner of our generation, recently dead, in a case suffering from fever and great thirst, when he learnt that the man had begun to feel oppressed after intoxication,[p. 39] administered cold water, by which draught, when by the admixture he had broken the force of the wine, he forthwith dispersed the fever by means of a sleep and a sweat.

Hippocrates Nutriment, introduction

A later Heraclitean, whether a professional doctor or not is uncertain, applied the theory of perpetual change to the assimilation of food by a living organism, and Nutriment is the result.

Apparently nutritive food is supposed to be dissolved in moisture, and thus to be carried to every part of the body, assimilating itself to bone, flesh, and so

Air (breath) also is regarded as food, passing through the arteries from the heart, while the blood passes through the veins from the liver. But the function of blood is not understood ; blood is, like milk, "what is left over" (πλεονας1μός2) when nourishment has taken place. Neither is the function of the heart understood, and its relation to the lungs is never mentioned. Hippocrates De morbo sacro

The brain of man, as in all other animals, is double, and a thin membrane (meninx)divides it through the middle, and therefore the pain is not always in the same part of the head; for sometimes it is situated on either side, and sometimes the whole is affected; and veins run toward it from all parts of the body, many of which are small, but two are thick, the one from the liver, and the other from the spleen. And it is thus with regard to the one from the liver: a portion of it runs downward through the parts on the side, near the kidneys and the psoas muscles, to the inner part of the thigh, and extends to the foot. It is called vena cava. The other runs upward by the right veins and the lungs, and divides into branches for the heart and the right arm. The remaining part of it rises upward across the clavicle to the right side of the neck, and is superficial so as to be seen; near the ear it is concealed, and there it divides; its thickest, largest, and most hollow part ends in the brain; another small vein goes to the right ear, another to the right eye, and another to the nostril. Such are the distributions of the hepatic vein. And a vein from the spleen is distributed on the left side, upward and downward, like that from the liver, but more slender and feeble.

De morbis popularibus, on the epidemics Phthisis: dwindling or wasting away, tuberculosis

IN THASUS, about the autumn equinox, and under the Pleiades, the rains were abundant, constant, and soft, with southerly winds; the winter southerly, the northerly winds faint, droughts; on the whole, the winter having the character of spring. The spring was southerly, cool, rains small in quantity. Summer, for the most part, cloudy, no rain, the Etesian winds, rare and small, blew in an irregular manner. The whole constitution of the season being thus inclined to the southerly, and with droughts early in the spring, from the preceding opposite and northerly state, ardent fevers occurred in a few instances, and these very mild, being rarely attended with hemorrhage, and never proving fatal. Swellings appeared about the ears, in many on either side, and in the greatest number on both sides, being unaccompanied by fever so as not to confine the patient to bed; in all cases they disappeared without giving trouble, neither did any of them come to suppuration, as is common in swellings from other causes. They were of a lax, large, diffused character, without inflammation or pain, and they went away without any critical sign. They seized children, adults, and mostly those who were engaged in the exercises of the palestra and gymnasium, but seldom attacked women. Many had dry coughs without expectoration, and accompanied with hoarseness of voice. In some instances earlier, and in others later, inflammations with pain seized sometimes one of [p. 101]the testicles, and sometimes both; some of these cases were accompanied with fever and some not; the greater part of these were attended with much suffering. In other respects they were free of disease, so as not to require medical assistance.

Early in the beginning of spring, and through the summer, and towards winter, many of those who had been long gradually declining, took to bed with symptoms of phthisis; in many cases formerly of a doubtful character the disease then became confirmed; in these the constitution inclined to the phthisical. Many, and, in fact, the most of them, died; and of those confined to bed, I do not know if a single individual survived for any considerable time….The urine was thin, colorless, unconcocted, or thick, with a deficient sediment, not settling favorably, but casting down a crude and unseasonable sediment.

n the course of the summer and autumn many fevers of the [p. 102]continual type, but not violent; they attacked persons who had been long indisposed, but who were otherwise not in an uncomfortable state.